The themes, activities, and approaches detailed in the tabs below offer you ideas and examples to enrich your online course design by integrating principles of Indigenous pedagogy. Each Theme draws attention to cross-connections with the 5Rs, and then offers you additional resources, examples and readings to explore and adapt.

Connecting with the 5Rs

- Relationships: How is this lesson/activity cultivating radical solidarity to support indigenous nations, as more than allies/accomplices to their cause?

- Respect: How does this lesson/activity acknowledging the complexity of decolonization and our complicity in impeding it?

- Relevance: How is this lesson/activity relevant to decolonizing education?

- Responsibility: How is this lesson/activity working towards Indigenous sovereignty and self-governance?

- Reciprocity: How is this lesson/activity committed to the repatriation of Indigenous land and life?

Resources

| Why decolonize online learning spaces? Visit The 5R’s: Decolonizing the online space to learn more. | |

| Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education. Society 1(1), 1–40. | |

|

Pedagogical examples:

|

(Regan, 2010, p. 16) |

|

| Shirley Anne Swelchalot qas te Shxwha:yathel Hardman speak about the simple message of reconciliation and how it asks for humility from us, as educators |

Connecting with the 5Rs

- Relationships: How is this lesson/activity providing opportunities to change and strengthen Indigenous-settler relations while addressing restitution and reparations for loss of land and Indigenous rights?

- Respect: How does this lesson/activity acknowledge the impacts of settler-colonialism to Indigenous peoples and prioritize improved educational outcomes for Indigenous peoples?

- Relevance: How is this lesson/activity relevant to the Truth and reconciliation commission of Canada: Calls to action?

- Responsibility: How is this lesson/activity rethinking practices and beliefs that influence what we teach and how we teach, allowing us to consider how we might better advance Indigenous ways of knowing in educational spaces?

- Reciprocity: How is this lesson/activity committed to truth telling and making space for collective critical dialogue?

Resources

|

Reconciliation Canada’s toolkit and Discussion Guide offer excellent resources. |

|

Regan, P. (2010). Unsettling the settler within: Indian residential schools, truth telling, and reconciliation in Canada. UBC Press. |

|

Learn more in UBC’s MOOC: Reconciliation through Indigenous education |

(Sam et al., 2021) |

|

| Dr. Johanna Sam describes how she embraced digital storytelling for learning and teaching |

Connecting with the 5Rs

- Relationships: How will sharing this story connect the listeners to the experiences of Indigenous peoples in order to hold themselves accountable to their complicity in the continuous violence Indigenous peoples encounter?

- Respect: Am I following protocols and practices that make me ready to share this story?

- Relevance: Are the digital stories that I am using relevant to Indigenous peoples, the context of the students and/or the land I am situated in?

- Responsibility: How is sharing this story committed to reconciliation, decolonization or/and Indigenous sovereignty?

- Reciprocity: How will sharing this story give back to the peoples/communities I am speaking of/for?

Resources

|

Visit the Grease Trail Digital Storytelling Project |

|

Sam, J., Schmeisser, C., & Hare, J. (2021). Grease Trail storytelling project: Creating Indigenous digital pathways. KULA: Knowledge Creation, Dissemination, and Preservation Studies, 5(1). |

| Learn More about Indigenous Storywork on Dr. Jo-ann Archibald’s website. |

(Wilson, 2021) |

|

| Dr. Jennifer MacDonald describes some of her approaches to land-based learning online. |

Connecting with the 5Rs

- Relationships: How will this learning provide opportunities to engage and cultivate relations with the land regardless of being in an online setting?

- Respect: How is this learning holding reverence towards land and waters?

- Relevance: How is this learning relevant to the land you are situated in?

- Responsibility: How is this learning holding us accountable and deepening our understanding of why we must and how we can protect the land?

- Reciprocity: How is this learning upholding the principle of giving back what we take from the land?

Resources

|

Explore the website of the Dechinta Centre for Research and Learning, an Indigenous land-based initiative |

| Wilson, A. (2021). Queering land-based education during Covid19. Journal of Global Indigeneity 5 (1), 1–10. | |

| Learn more in the Dechinta report Indigenous land-based education in the era of COVID-19. |

(Battiste, 2002, p. 15) |

|

| “First Nations Experiential Learning Cycle” from First Nations Pedagogy Online. |

Connecting with the 5Rs

- Relationships: How will this experiential learning provide opportunities to engage and cultivate relations?

- Respect: Am I following protocols and practices that hold me accountable to facilitate this experiential learning?

- Relevance: How is this experiential learning relevant to Indigenous ways of knowing and being?

- Responsibility: What are the philosophical and spiritual traditions of this experiential learning? Where did it come from?

- Reciprocity: How is this experiential learning upholding principles of mutual accountability and solidarity?

Resources

|

O’Connor, K. B. (2009). Northern exposures: Models of experiential learning in Indigenous education. Journal of Experiential Education, 31(3), 415–419. |

|

Learn more about experiential learning at Experiential education at UBC |

|

|

Connecting with the 5Rs

- Relationships: How will this multimodal learning activity provide opportunities to engage and cultivate relations?

- Respect: How is this multimodal learning activity in alignment with Indigenous ways of learning?

- Relevance: How is this multimodal learning activity relevant to Indigenous ways of knowing and being?

- Responsibility: How is this multimodal learning activity giving space for students to express their understanding in meaningful ways?

- Reciprocity: How is this multimodal learning activity mutually beneficial to both the student and the learning community?

Resources

|

Learn more about Indigenous pedagogy and multimodal learning on the Indigenous Ways to Multimodal Literacy website |

|

Mills, K. & Doyle, K. (2019). Visual arts: A multimodal language for Indigenous education, Language and Education, 33:6, 521-543, |

|

Pedagogical examples:

|

(Archibald, 2008, p. 67)

|

|

| Dr. Angelina Weenie discusses how and why she involves Elders in her work and in her online teaching. |

Connecting with the 5Rs

- Relationships: How will this learning provide opportunities to engage with and cultivate intergenerational relations?

- Respect: Am I following protocols and practices to include intergenerational teachings in a good way?

- Relevance: Is it relevant to bring intergenerational teachings to my lesson design?

- Responsibility: Have I created an ethical space where all are held accountable to receive intergenerational teachings in a good way?

- Reciprocity: How is this intergenerational learning beneficial to both the student and community?

Resources

|

Read Elders’ Teachings on Jo-ann Archibald’s Indigenous Storyworks website. |

| McLeod, Y. G. (2012). Learning to lead Kokum style: An intergenerational study of eight first nation women. In Kenny, C., Ngaroimata Fraser, T. (Eds.), Living Indigenous leadership: Native narratives on building strong communities (pp. 17–47). UBC Press. | |

| Explore As I remember it: Teachings (Ɂəms tɑɁɑw) from the life of a Sliammon Elder |

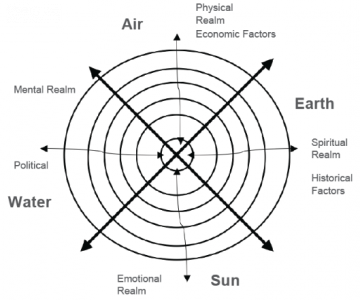

(Absolon, 2019)

|

|

| One version of a Medicine Wheel framework (from Absolon, 2019) |

Connecting with the 5Rs

- Relationships: How will this holistic learning provide opportunities to create a harmonious healthy learning community?

- Respect: How does this holistic learning acknowledge Indigenous ways of learning and revere where the knowledge comes from?

- Relevance: How is this holistic learning relevant to Indigenous ways of knowing and being?

- Responsibility: How is this holistic learning honouring Indigenous teachings and traditional practices?

- Reciprocity: How is this holistic learning interrelated between the intellectual, spiritual, emotional and physical dimensions?

Resources

|

Bell, N. (2014, June 9). Teaching by the medicine wheel: An Anishinaabe framework for Indigenous education. EdCan Network. |

|

Pedagogical examples:

|

|

Learn More: Absolon, K. (2019). Indigenous wholistic theory: A knowledge set for practice. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 14(1), 22-42. |

(Corson, 1998, p. 240) |

|

| Dr. Jo-ann Archibald speaks about the importance of integrating community engagement throughout our scholarly and teaching work. |

Connecting with the 5Rs

- Relationships: How is this lesson/activity engaging in respectful relations and appropriate ways to support local communities?

- Respect: How is this lesson/activity acknowledging the complexity and impact of historical educational approaches for community engagement?

- Relevance: How is this lesson/activity relevant to local communities?

- Responsibility: How is this lesson/activity listening to and supporting communities’ priorities, as well as consulting and collaborating with them?

- Reciprocity: How is this learning giving back to the community we are learning from?

Resources

|

Corson, D. (1998). Community-based education for Indigenous cultures. Language Culture and Curriculum, 11(3), 238-249. |

|

This video (24 mins.) by the BC Principals’ & Vice-Principals’ Association offers perspectives on how schools can respectfully build bridges with Aboriginal communities in support of student achievement. |

(Augustine, 2008, p. 2-3) |

|

| Shirley Anne Swelchalot qas te Shxwha:yathel Hardman speaks about listening and speaking in learning. |

Connecting with the 5Rs

- Relationships: How will sharing this oral tradition connect the listeners to the experiences of Indigenous peoples in order to hold themselves accountable to their complicity in the continuous violences Indigenous peoples encounter?

- Respect: Am I following protocols and practices that make me ready to share this oral tradition?

- Relevance: How is this oral tradition relevant to Indigenous ways of knowing and being?

- Responsibility: How is sharing this oral tradition committed to reconciliation, decolonization or/and Indigenous sovereignty?

- Reciprocity: How will sharing this oral tradition give back to the peoples/communities I am speaking of/for?

Resources

|

Learn about podcasting as an approach to capturing and sharing spoken word, on Teachings in the Air’s Podcasting at home website. |

| Augustine, S. J. (2008). Oral histories and oral traditions. In R. Hulan & R. Eigenbrod (Eds.), Aboriginal oral traditions: Theory, practice, ethics (pp. 2–3). Halifax: Fernwood Publishing. | |

| Learn more in the Indigenous oral Histories and primary sources section of The Canadian Encyclopedia. |